Remember When the Olympics Used to Have an Art Competition? No?

Yes, the Olympics once had an art division—and in 1936, it was kind of hijacked by Nazis.

Yes, the Olympics once had an art division—and in 1936, it was kind of hijacked by Nazis.

Once upon a time, you could win a medal for art in the Olympics.

Yes, really. You could leave the Olympics with a heavy souvenir hanging around your neck for having sculpted the best Greek wrestler, or painted the best scenic watercolor of rowing crews sculling at dawn. And if the father of the modern Olympic Games had had his way, you'd still be able to.

It was International Olympic Committee founder Pierre de Coubertin's great dream to marry the aesthetic with the athletic—thus, every Olympics between 1912 and 1948 awarded gold, silver, and bronze medals to artists. There were five categories of individual competition: Architecture, painting, sculpture, literature, and music. Artworks were required by official Olympic rules to "bear a definite relationship to the Olympic concept." Musical compositions, for example, which "glorified a sporting ideal, an athletic competition or an athlete, or which were intended for presentations in connection with sporting festivals" could be entered for review and evaluation by an international jury. Other curious specifications include a 20,000-word limit on literature entries (a category divided into dramatic works, lyrical works, and epic poetry) and a one-hour time allotment for the presentation of each musical work.

Under these guidelines, it's amusing to imagine who might be winning medals today if the Olympics were still holding art competitions. "LeRoy Neiman, the painter known for his celebratory images of sports greats, might well have been... the Michael Phelps of oils," New York Times writer Charles Isherwood remarked on the subject in 2010. "Might the lyric winner for the 1998 Winter Olympics have been a tribute to the infamous skating scandal of the previous games, something titled 'The Ballad of Tonya and Nancy'?"

There's a reason, though, why so few of us have ever heard of these Olympic art competitions. Art history and Olympic history both largely glossed over them because, to put it simply, they had little impact on either one. Few artists of note ever competed in the Olympic art competitions because professional artists were prohibited from entering; thus, among the best-known winners of Olympic medals for art are the American architect Charles Downing Lay and one Joseph Webster Golinkin, a lithographer whose oeuvre included designs for a number of American stamps.

Many details of the art contests (and many medal-winning artists) have receded into oblivion over the years because of the lack of attention and documentation the art division of the Games received.

When the Olympic historian Bernhard Kramer went in search of these lost Olympic art champions, he concluded that, sadly, a large portion of the medal-winning artists and artworks had been lost to history. His ensuing paper is strewn with the likes of "No documentary evidence can be given at the moment," "Her poem is also lost," and "A reproduction of Gerhardus Bernardus Westermann's bronze medal-winning painting Horseman could not be found."

Among the best-documented Olympic art competitions, however, is the one held at the 1936 Summer Games in Berlin.

1936: AN ART COMPETITION TO REMEMBER

MORE ON THE OLYMPICS

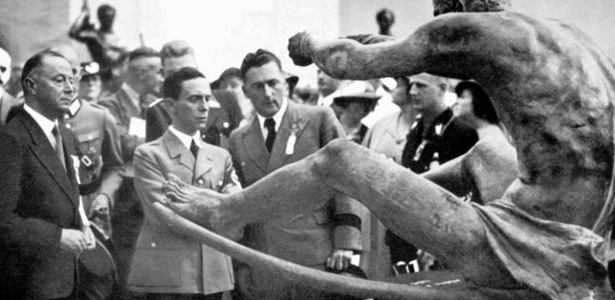

At the opening ceremony of 1936 Olympic art competition, Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels reminded his audience that each work entered in the competition was required to have been created within the last four years. This restriction, he declared, "enables us to derive from the Exhibition an estimate of international conditions."

Enable us it did. The detailed descriptions in the Official Report of the 11th Olympic Games not only provide a dazzling depiction of this charmingly peculiar Olympic-art phenomenon, but also a chilling snapshot of Germany during the emergence of the Third Reich.

Home-field advantage, it seems, greatly worked in Germany's favor that year. The international jury consisted of 29 German judges and 12 from other European countries. What little evidence exists suggests that very few other host nations so generously populated their international juries with their own nationals, with one noteworthy exception: In 1932, the United States included 24 American judges in a panel of 30—to a similarly victorious effect.

It was also a welcome, if not surprising, spike in gold medals for the German artists, who won five of the nine gold medals awarded that year. (By contrast, their combined gold-medal count from the 1928 and 1932 Summer Olympics had come to a grand total of one.) German musicians also swept the Musical Composition for Solo and Chorus category.

Charles Downing Lay was the only American to win a medal in 1936, taking home silver in the Municipal Planning division of the Architecture category for his design titled "Marine Park in Brooklyn." A pair of German brothers called Werner and Walter March took home gold in that category for their design "Reich Sport Field." The latter was based on the Olympiastadion, an original structure designed by Werner that had been built to scale right there in Berlin over the course of the previous two years. It was currently housing the Olympic competitions in handball, equestrian, soccer, and track and field, and in fact, it's still in use today.

GLITCHES IN THE PROGRAMMING

The German organizers of the 1936 Games did, of course, run into their share of problems in putting together an art competition; for starters, the German people distinctly lacked interest in it.

But according to the Official Report, that was nothing a little propaganda campaign couldn't fix:

Because of the slight interest which the general public had hitherto evidenced in the Olympic Art Competition and Exhibition, it was necessary to emphasize their cultural significance to the Olympic Games through numerous articles in the professional and daily publications as well as radio lectures.

At the same time an appropriate poster had to be designed in order to attract as many visitors as possible. ... The poster [designed by Dresden artist Willy Petzold], which revealed an antique head wearing a victor's band, was printed in a rich bronze, and 7,000 copies were displayed in the stations of the state, underground and municipal railways in addition to the Berlin museums, hotels, theatres, restaurants, cafes and shops. It proved to be extremely effective and contributed in no small degree to the surprising success of the Exhibition.

Still, other issues lurked. Due dates for art competition entries had to be extended that year; as a result of "special conditions existing in several nations and the consequent uncertainty of whether they would participate in the Olympic Games," the deadlines were pushed back four weeks into the late spring of 1936. A quick consultation of the historical accounts of the months leading up to the Summer Olympics provides a clue as to what those "special conditions" may have been—though boycott movements in Great Britain, France, Sweden, Czechoslovakia, and the Netherlands had been abandoned soon after the United States decided to compete in December of 1935, countries like the Soviet Union and Spain were still holding fast to their promises to skip the Games. (That deadline extension proved beneficial, however, to the U.S. Olympic art effort: The extra time allowed the French ambassador Charles Sherrill, an Olympic art enthusiast and IOC member, to successfully coax American expatriate artists living in Paris to enter their work into the competition.)

The 1936 art competition, though, despite its initial struggles, was one of the most successful on record. More than 70,000 people visited the accompanying exhibition over the course of its four weeks on display. Prominent citizens like the Reich Ministers Frick, Goebbels, and Rust, the Italian Minister of Education, and the Baron Morimoura of Japan all purchased works from the exhibition. And the Reich, according to the Official Report, "generously arranged for the transference of the sums realized from the sale of art objects without the usual formalities."

THE END OF THE OLYMPIC ART COMPETITIONS

What ultimately brought about a full overhaul of the sporting divisions of the Olympic Games is what crippled and eventually killed its artistic counterpart: the amateurism dilemma. Professional artists were barred from the competition, in keeping with the rules that also governed the sport events of the Games. The athletic events would later radically evolve to accommodate professional athletes, but the art competitions were less receptive to the inclusion of professionals; formal Olympic documents would later deem it "illogical that professionals should compete at such exhibitions and be awarded Olympic medals" and attribute the art contests' demise to complications in determining the amateur status of the artists.

The amateurism decree also severely undermined the quality of the entrant pools—and the entries themselves. Creating an engaging piece of Olympics-inspired art is a notoriously difficult task, and taking away professionals' right to try their hands at it didn't help. Olympic juries in those days had the right to withhold a first-, second-, or third-place prize (or all of the above) when works failed to meet the standards they imposed; juries were known to withhold as many as 13 art medals in a single Olympics, and it's not hard to imagine that each "no prize awarded" was in itself a tiny, spiteful act of protest by these elite clusters of art critics and professors.

After the 1948 games, the Olympic art competitions were modified into a parallel art festival and exhibition held at the site of each Summer and Winter Games.

The lack of existing resources on the topic makes it difficult to say what exactly these art competitions meant to the international art community, or to the Olympics. (Or perhaps that paucity itself indicates precisely what degree of lasting impact they had—very little.) Were the Olympic art contests a failed experiment, or simply a curious little relic of an age and an ideology that came and went? The answer to that question, like Gerhardus Bernardus Westermann's Horseman, may be lost to the unyielding passage of time.